The Neuroscience Behind Brain Death

- myakamara

- Feb 14, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Mar 6, 2024

In the medical field, there has long been a debate on the concept of death: When does a person actually die? When is a person pronounced clinically dead? This discussion hinges on the distinctions between biological death and clinical death. Biological death refers to the irreversible cessation of all biological functions necessary to sustain life, traditionally marked by the cessation of heart and respiratory functions. Clinical death, on the other hand, occurs when heart and respiratory functions stop, but resuscitation may still be possible if initiated promptly. The introduction of the concept of brain death in the past century has added complexity to these definitions, necessitating a deeper understanding within the medical community and society at large.

Following the creation of advanced life support technologies such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and positive pressure ventilation (PPV), the traditional criteria for defining death began to face scrutiny. This reevaluation was propelled in 1959 when Mollaret and Goulon introduced the notion of "le coma dépassé," describing patients in a coma with no brainstem reflexes or signs of brain activity on an EEG, essentially theorizing the concept of brain death or death by neurologic criteria (BD/DNC). This led neurologists to reconsider the importance of neurologic function over cardiopulmonary function, initiating efforts to neurologically define death, separate from the functionality of other critical organs.

By 1968, a pivotal moment arrived when Harvard faculty members introduced the initial clinical definition with the Harvard Brain Death Criteria, incorporating both clinical assessments and EEG findings. The Harvard Committee defined "the traits of a permanently (with original emphasis) nonfunctional brain" as consisting of three main criteria: (1) a lack of receptivity and responsiveness, (2) no movements or breathing, and (3) the absence of reflexes. The establishment of a neurological basis for declaring death was further solidified in 1980 with the Uniform Determination of Death Act in the U.S., providing a legal framework for neurologically determining death. Subsequent guidelines tailored for adults were released in 1995 by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), with revisions made in 2010, marking significant milestones in the formalization of BD/DNC. Additionally, the American Academy of Pediatrics set forth specific guidelines for diagnosing brain death in children in 1987, with updates following in 2011, acknowledging the need for age-specific criteria in the pediatric population.

What Exactly is Brain Death?

The "whole brain" approach is the most universally embraced standard for defining brain death. It equates brain death with the extensive and irreversible damage to all critical areas of the brain, including the hemispheres, diencephalon, brainstem, and cerebellum. According to this perspective, it's essential to verify that the entire brain has suffered complete and irrevocable harm before formally recognizing BD/DNC (Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria). This principle forms the basis of the original Harvard criteria for brain death and is the preferred definition endorsed by the United States (U.S.) and the majority of countries that have established national guidelines for brain death. Additionally, this approach is supported by the World Brain Death Project, an initiative by leading researchers and international professional organizations dedicated to creating uniform global standards and achieving worldwide agreement on the criteria for determining BD/DNC (Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria)..

The term "brain death",often surrounded by discussion and differing viewpoints, is crucial to grasp for a well-rounded understanding by the general public, medical professionals, and legal authorities. The terminology itself varies, with phrases like "whole brain death" or "brainstem death" being used interchangeably. However, to ensure clarity and consensus, many experts prefer the term BD/DNC.

Defining Brain Death

Supporters of using neurologic criteria to define brain death emphasize the concept that an individual is more than just a collection of physical parts. They argue that true death reflects the loss of what constitutes the person as a whole, particularly pointing out that individual organs, like a kidney or a limb, can be lost without resulting in death. It's the brain, they argue, that is central to our identity, consciousness, and the integrated functioning of our body. The brain acts as the command center for critical life-sustaining functions, including those that regulate our heart and lungs. Therefore, when the brain stops working, these vital processes will ultimately fail as well. In medical practice, accurately diagnosing BD/DNC is vital for the process of organ donation, especially for heart transplants in the United States, where donors declared brain dead are the primary source. However, it's crucial to recognize that diagnosing BD/DNC is a significant medical judgment made independently of any considerations for organ donation.

Importance of Neuroimaging when Defining Brain Death - Example

Patient arrived at the emergency department after experiencing a cardiac arrest, likely triggered by an acute coronary ischemia syndrome.

Following more than 30 minutes of advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), the team successfully restored spontaneous circulation.

The initial neurological examination showed the patient in a coma with fixed, dilated pupils and a complete absence of brainstem reflexes, with no sedative drugs administered.

The first CT scan upon admission indicated diffuse anoxic brain damage while still showing intact cerebral and brainstem structures without any signs of herniation.

Approximately 36 hours after admission, there was no sign of clinical improvement in the patient, prompting a subsequent CT scan.

This scan showed a significant increase in diffuse cerebral edema and bilateral uncal herniation. Based on these neuroimaging findings, which closely corresponded with the patient's clinical presentation.

BD/DNC (Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria) was conclusively diagnosed.

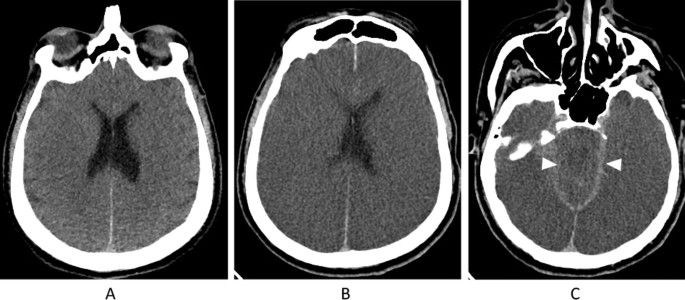

The initial non-contrast CT scan labeled as Image A, taken shortly after the patient experienced a cardiac arrest, revealed early signs of brain damage. This was indicated by the blurring of lines between the grey matter (the part of the brain responsible for processing information) and white matter (the parts that connect different brain regions), which should normally be distinct in the cerebral cortex.

The subsequent scans, labeled as Images B and C, conducted 36 hours later, showed an advancement of this condition. The blurring between grey and white matter now extended to include the brainstem, an area crucial for controlling vital life functions such as breathing and heart rate. Alongside this, there was a noticeable increase in cerebral edema, meaning the brain was swelling significantly. This swelling led to the pressing together and obliteration of the brain's folds (known as sulci) and the internal fluid chambers (ventricles), making them less visible. Also, the compression of the basilar cisterns, which are fluid-filled spaces at the brain's base, was observed. These changes, highlighted in the follow-up images B and C, illustrate the severe and widespread impact of the brain injury, helping to convey the gravity of the patient's situation in a more understandable way for those unfamiliar with medical terminology.

Clinical Examination for Determining Brain Death

The process of clinically determining BD/DNC (Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria) is complex and challenging, even for seasoned neurologists and critical care specialists. Achieving an accurate diagnosis is critical, given that the procedure for confirming brain death involves numerous meticulous steps. Despite these challenges, with adequate training, preparation, and the employment of checklists, the accuracy of diagnosis can be consistently ensured. The importance of an infallible determination of death cannot be overstated. As Shewmon (2017) notes, unlike other medical tests that balance sensitivity and specificity, the diagnosis of death requires absolute certainty: it must have 100% specificity with absolutely no margin for error in falsely declaring someone dead.

This process is governed by strict protocols to ensure the diagnosis is accurate and ethically sound. Below is a detailed description of the tests and criteria involved in diagnosing brain death:

Initial Considerations

Before commencing the brain death evaluation, certain preliminary conditions must be satisfied to ensure the validity of the assessment:

Confirmation of a Neurological Cause: The medical team must identify a clear neurological reason for the patient's condition, such as severe brain injury or catastrophic cerebral event.

Exclusion of Confounding Factors: It's critical to rule out any reversible conditions that could mimic brain death, including drug intoxication, hypothermia (body temperature significantly below normal), or metabolic disturbances.

Optimization of Physiological Parameters: The patient must be hemodynamically stable, with normal or corrected blood pressure, electrolyte levels, acid-base balance, and no severe endocrine abnormalities.

Comprehensive Neurological Examination

A detailed neurological examination is the cornerstone of the brain death assessment, comprising:

Assessment of Consciousness: The patient must exhibit no signs of awareness or consciousness, with a complete absence of responsiveness to external stimuli, including pain.

Evaluation of Brainstem Reflexes: A series of tests are conducted to assess the presence of brainstem reflexes, as their absence indicates non-functioning of the brainstem:

- Pupillary Reflex: Checking for any pupil reaction to light. In brain death, pupils are fixed in diameter and do not respond to light.

- Oculocephalic Reflex (Doll’s Eyes): Observing eye movements in response to head turning. The absence of eye movement suggests brainstem dysfunction.

- Oculovestibular Reflex (Caloric Test): After ensuring eardrums are intact, cold water is injected into each ear canal sequentially to test for eye movement. No response is expected in brain death.

- Corneal Reflex: Touching the cornea with a wisp of cotton to test for blinking. No blinking indicates an absence of this reflex.

- Gag Reflex: Stimulating the back of the throat to observe any gagging motion. Its absence is noted in brain death.

- Cough Reflex: Attempting to elicit a cough by suctioning through the trachea. The lack of a cough reflex supports brain death.

- Apnea Test: This critical test measures the ability to initiate breathing autonomously when carbon dioxide levels rise, signifying drive to breathe:

- The patient is pre-oxygenated, and then mechanical ventilation is temporarily halted under controlled conditions.

- Blood gas analyses are performed to confirm a significant rise in carbon dioxide levels without any respiratory effort from the patient, indicating an absence of brainstem function.

Ancillary Testing

When the clinical examination and apnea test do not conclusively demonstrate brain death, or when parts of the exam cannot be performed, additional tests are used:

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Demonstrates electrical activity in the brain. A flat EEG, indicating no electrical activity over a specified period, supports the diagnosis of brain death.

- Cerebral Blood Flow Studies: Techniques such as radionuclide angiography, Doppler ultrasonography, or cerebral angiography can assess the absence of cerebral blood flow.

- Advanced Neuroimaging: CT Angiography (CTA), Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), or perfusion scans can provide evidence of no blood flow to the brain, further corroborating the absence of brain function.

Documentation, Review, and Confirmation

- Detailed documentation of each step of the process, findings, and the conclusions drawn is essential for legal and medical records.

- A repeat examination, often by another physician, may be required after a certain period to ensure the irreversibility of brain death. This period varies based on specific guidelines and the patient's condition.

Why is this Important?

This rigorous and methodical approach ensures that the determination of brain death is made with the highest degree of certainty. The diagnosis of brain death has profound implications for end-of-life care decisions, organ donation, and ethical considerations, necessitating a procedure that is thorough, precise, and conducted with the utmost professionalism and sensitivity.

Example Video - "Brain Death Testing Demo"

Ethical and Legal Considerations of Brain Death

The legal and ethical considerations surrounding brain death are complex and multifaceted, touching on profound questions about life, death, and personhood. Legally, brain death is recognized in many jurisdictions as equivalent to cardiac death, allowing for the cessation of life-sustaining treatments and making organ donation possible. Ethically, it raises debates on the dignity of the individual, consent for organ donation, and the responsibilities of healthcare providers. Balancing respect for the wishes of the deceased and their families with medical and societal needs is a delicate task, requiring clear communication, compassionate care, and adherence to rigorous medical criteria.

The integration of advanced medical technologies allowing for the maintenance of bodily functions after the brain has ceased all activity (artificial life support) has pushed the topic of brain death into the spotlight of both academic debate and public interest. This attention has been amplified by high-profile legal cases, leading to increased discussions about brain death among both the general public and medical professionals. Surveys indicate a significant number of neurologists encounter requests from families to continue medical interventions for patients diagnosed as brain-dead, occasionally leading to legal challenges. These legal confrontations have resulted in a mix of judgments, creating uncertainty and variability in protocols across different jurisdictions. This situation underscores the complex interplay between the scientific understanding of brain death and its perception and implications within society, affecting expectations around end-of-life care.

Stories

The Jahi McMath case in 2013 sharply highlights disparities in state laws regarding brain death. After a tonsillectomy led to severe complications, McMath, then 13, was declared brain dead in California, after suffering an anoxic brain injury from massive hemorrhage and cardiac arrest after a routine tonsillectomy at Children’s Hospital Oakland. She was declared brain dead at the treating hospital on December 12, 2013, a decision her family contested. They pursued legal avenues to maintain cardiopulmonary (life) support, and the Superior Court of Alameda County determined Jahi McMath was legally deceased. This verdict was contested in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, resulting in an agreement to hand over McMath, along with her life-support equipment, to her mother's care. Subsequently, McMath was moved to New Jersey for further treatment, where she underwent medical procedures until organ failure led to the cessation of ventilator support in January 2018, culminating in the issuance of a second death certificate. Post-McMath, numerous legal actions have been initiated, seeking similar accommodations in places with more lenient brain death standards. leading to a court decision allowing her transfer to New Jersey, a state with laws that accommodated their position. In New Jersey, she received further medical interventions until her eventual passing in 2018 due to organ failure. This case has prompted other families to seek similar legal remedies in jurisdictions with less stringent definitions of brain death.

On a day in late November of 2013, Erick Muñoz discovered his wife, Marlise Muñoz, unconscious at their home and immediately took her to John Peter Smith Hospital, suspecting a pulmonary embolism. It was there they learned she was 14 weeks pregnant. Marlise, who worked as a paramedic like Erick, had expressed a wish not to be kept alive by machines in the event of brain death—a state confirmed by the hospital shortly after her admission. Despite this, when Erick sought to cease life-sustaining treatment, the hospital cited Texas's specific legislation on pregnant patients, leading Erick to challenge this decision legally. In early 2014, Erick Muñoz's legal team highlighted the fetus's significant abnormalities and potential non-viability due to oxygen deprivation, including hydrocephalus and potential heart issues, complicating the case against life support continuation under Texas law. Judge R. H. Wallace Jr. decreed the hospital must end organ support for Marlise by January 27, emphasizing the law's inapplicability to deceased individuals. This case spotlighted the tension between state laws on life support for pregnant patients and personal medical directives, culminating in Marlise's life support cessation and her family's poignant tribute by naming the fetus Nicole.

Conclusion

The exploration of brain death in medical science involves advancing research into brain function and recovery potential, alongside technological innovations in monitoring and diagnosing. This evolution challenges existing definitions and criteria, indicating a need for possible reevaluation. The significance of understanding brain death extends beyond the medical field, affecting societal views on life support and patient rights. Ongoing debates highlight the intricate relationship between medical ethics, legal frameworks, and personal values.For more information, I recommend searching through reputable medical and ethical journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association), and the American Journal of Bioethics. Websites like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and organizations such as the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and Donate Life America offer valuable resources.

Comments